Norton Priory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norton Priory is a historic site in

The site for the new priory was in damp, scrubby woodland. There is no evidence that it was agricultural land, or that it contained any earlier buildings. The first priority was to clear and drain the land. There were freshwater springs near the site, and these would have provided fresh running water for latrines and domestic purposes. They would also have been used to create watercourses and

The site for the new priory was in damp, scrubby woodland. There is no evidence that it was agricultural land, or that it contained any earlier buildings. The first priority was to clear and drain the land. There were freshwater springs near the site, and these would have provided fresh running water for latrines and domestic purposes. They would also have been used to create watercourses and

The abbey's fortunes went into decline after the death of Richard Wyche in 1400. Wyche was succeeded by his

The abbey's fortunes went into decline after the death of Richard Wyche in 1400. Wyche was succeeded by his

In 1545 the abbey and the manor of Norton were sold to Sir Richard Brooke for a little over £1,512 (). Brooke built a house in Tudor style, which became known as Norton Hall, using as its core the former abbot's lodgings and the west range of the monastic buildings. It is not certain which other monastic buildings remained when the abbey was bought by the Brookes; excavations suggest that the

In 1545 the abbey and the manor of Norton were sold to Sir Richard Brooke for a little over £1,512 (). Brooke built a house in Tudor style, which became known as Norton Hall, using as its core the former abbot's lodgings and the west range of the monastic buildings. It is not certain which other monastic buildings remained when the abbey was bought by the Brookes; excavations suggest that the  At some time between 1727 and 1757 the Tudor house was demolished and replaced by a new house in

At some time between 1727 and 1757 the Tudor house was demolished and replaced by a new house in  By 1853 a service range had been added to the south wing of the house. In 1868 the external flight of stairs was removed from the west front and a new porch entrance was added to its ground floor. The entrance featured a

By 1853 a service range had been added to the south wing of the house. In 1868 the external flight of stairs was removed from the west front and a new porch entrance was added to its ground floor. The entrance featured a

The earliest masonry building was the church, which was constructed on shallow foundations of

The earliest masonry building was the church, which was constructed on shallow foundations of

The excavations revealed information about the burials carried out within the church and the monastic buildings, and in the surrounding grounds. They are considered to be "either those of Augustinian canons, privileged members of their lay household, or of important members of the Dutton family". Most burials were in stone coffins or in wooden coffins with stone lids, and had been carried out from the late 12th century up to the time of the dissolution. The site of the burial depended on the status of the individual, whether they were clerical or lay, and their degree of importance. Priors, abbots, and high-ranking canons were buried within the church, with those towards the east end of the church being the most important. Other canons were buried in a graveyard outside the church, in an area to the south and east of the chancel. Members of the laity were buried either in the church, towards the west end of the nave or in the north aisle, or outside the church around its west end. It is possible that there was a lay cemetery to the north and west of the church. The addition of the chapels to the north transept, and their expansion, was carried out for the Dutton family, making it their burial chapel, or family

The excavations revealed information about the burials carried out within the church and the monastic buildings, and in the surrounding grounds. They are considered to be "either those of Augustinian canons, privileged members of their lay household, or of important members of the Dutton family". Most burials were in stone coffins or in wooden coffins with stone lids, and had been carried out from the late 12th century up to the time of the dissolution. The site of the burial depended on the status of the individual, whether they were clerical or lay, and their degree of importance. Priors, abbots, and high-ranking canons were buried within the church, with those towards the east end of the church being the most important. Other canons were buried in a graveyard outside the church, in an area to the south and east of the chancel. Members of the laity were buried either in the church, towards the west end of the nave or in the north aisle, or outside the church around its west end. It is possible that there was a lay cemetery to the north and west of the church. The addition of the chapels to the north transept, and their expansion, was carried out for the Dutton family, making it their burial chapel, or family  A total of 144 graves was excavated; they contained 130 articulated skeletons in a suitable condition for examination. Of these, 36 were well-preserved, 48 were in a fair condition and 46 were poorly preserved. Males out-numbered females by a ratio of three to one, an expected ratio in a monastic site. Most of the males had survived into middle age (36–45 years) to old age (46 years or older), while equal numbers of females died before and after the age of about 45 years. One female death was presumably due to a complication of pregnancy as she had been carrying a 34-week

A total of 144 graves was excavated; they contained 130 articulated skeletons in a suitable condition for examination. Of these, 36 were well-preserved, 48 were in a fair condition and 46 were poorly preserved. Males out-numbered females by a ratio of three to one, an expected ratio in a monastic site. Most of the males had survived into middle age (36–45 years) to old age (46 years or older), while equal numbers of females died before and after the age of about 45 years. One female death was presumably due to a complication of pregnancy as she had been carrying a 34-week

A large number of tiles and tile fragments that had lined the floor of the church and some of the monastic buildings were found in the excavations. The oldest tiles date from the early 14th century. The total area of tiles discovered was about , and is "the largest area of a floor of this type to be found in any modern excavation". The site has "the largest, and most varied, excavated collection of medieval tiles in the North West" and "the greatest variety of individual mosaic shapes found anywhere in Britain". The tiles found made a pavement forming the floor of the choir of the church and the transepts. The chancel floor was probably also tiled; these tiles have not survived because the chancel was at a higher level than the rest of the church, and the tiles would have been removed during subsequent gardening. A dump of tiles to the south of the site of the chapter house suggests that this was also tiled. In the 15th century a second tile floor was laid on top of the original floor in the choir where it had become worn. The tiles on the original floor were of various shapes, forming a

A large number of tiles and tile fragments that had lined the floor of the church and some of the monastic buildings were found in the excavations. The oldest tiles date from the early 14th century. The total area of tiles discovered was about , and is "the largest area of a floor of this type to be found in any modern excavation". The site has "the largest, and most varied, excavated collection of medieval tiles in the North West" and "the greatest variety of individual mosaic shapes found anywhere in Britain". The tiles found made a pavement forming the floor of the choir of the church and the transepts. The chancel floor was probably also tiled; these tiles have not survived because the chancel was at a higher level than the rest of the church, and the tiles would have been removed during subsequent gardening. A dump of tiles to the south of the site of the chapter house suggests that this was also tiled. In the 15th century a second tile floor was laid on top of the original floor in the choir where it had become worn. The tiles on the original floor were of various shapes, forming a  The excavations also revealed stones or fragments of carved stone dating from the 12th to the 16th centuries. The earliest are in Romanesque style and include two

The excavations also revealed stones or fragments of carved stone dating from the 12th to the 16th centuries. The earliest are in Romanesque style and include two

The museum contains information relating to the history of the site and some of the artefacts discovered during the excavations. These include carved coffin lids, medieval mosaic tiles, pottery, scribe's writing equipment and domestic items from the various buildings on the site such as buttons, combs and wig curlers. Two medieval skeletons recovered in the excavations are on display, including one showing signs of

The museum contains information relating to the history of the site and some of the artefacts discovered during the excavations. These include carved coffin lids, medieval mosaic tiles, pottery, scribe's writing equipment and domestic items from the various buildings on the site such as buttons, combs and wig curlers. Two medieval skeletons recovered in the excavations are on display, including one showing signs of

The archaeological remains are recognised as a Grade I

The archaeological remains are recognised as a Grade I  At the northern end of the undercroft is the passage known as the outer parlour. This has stone benches on each side and elaborately carved blind arcades above them. The arcades each consist of two groups of four round-headed arches with

At the northern end of the undercroft is the passage known as the outer parlour. This has stone benches on each side and elaborately carved blind arcades above them. The arcades each consist of two groups of four round-headed arches with

The of grounds surrounding the house have been largely restored to include the 18th-century pathways, the stream-glade and the 19th-century rock garden. The foundations exposed in the excavations show the plan of the former church and monastic buildings. In the grounds is a Grade II listed garden

The of grounds surrounding the house have been largely restored to include the 18th-century pathways, the stream-glade and the 19th-century rock garden. The foundations exposed in the excavations show the plan of the former church and monastic buildings. In the grounds is a Grade II listed garden

The 3.5 acre (1 ha)

The 3.5 acre (1 ha)

Official website

History of the Priory

Norton Priory Walled Garden

Aerial photograph

Victoria County History

{{featured article Augustinian monasteries in England Monasteries in Cheshire Religious organizations established in the 1110s Ruins in Cheshire Norman architecture in England Tourist attractions in Cheshire Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire Grade I listed monasteries Archaeological sites in Cheshire 1536 disestablishments in England English Civil War Buildings and structures in Runcorn Scheduled monuments in Cheshire Christian monasteries established in the 12th century Museums in Cheshire Archaeological museums in England British country houses destroyed in the 20th century 1115 establishments in England

Norton Norton may refer to:

Places

Norton, meaning 'north settlement' in Old English, is a common place name. Places named Norton include: Canada

*Rural Municipality of Norton No. 69, Saskatchewan

*Norton Parish, New Brunswick

**Norton, New Brunswick, a ...

, Runcorn

Runcorn is an industrial town and cargo port in the Borough of Halton in Cheshire, England. Its population in 2011 was 61,789. The town is in the southeast of the Liverpool City Region, with Liverpool to the northwest across the River Mersey. ...

, Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, England, comprising the remains of an abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

complex dating from the 12th to 16th centuries, and an 18th-century country house; it is now a museum. The remains are a scheduled ancient monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

and are recorded in the National Heritage List for England

The National Heritage List for England (NHLE) is England's official database of protected heritage assets. It includes details of all English listed buildings, scheduled monuments, register of historic parks and gardens, protected shipwrecks, an ...

as a designated Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

. They are considered to be the most important monastic remains in Cheshire.

The priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of mon ...

was established as an Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

foundation in the 12th century, and was raised to the status of an abbey in 1391. The abbey was closed in 1536, as part of the dissolution of the monasteries. Nine years later the surviving structures, together with the manor of Norton, were purchased by Sir Richard Brooke, who built a Tudor house on the site, incorporating part of the abbey. This was replaced in the 18th century by a Georgian

Georgian may refer to:

Common meanings

* Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

** Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

** Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

**Georgian scripts, three scrip ...

house. The Brooke family left the house in 1921, and it was partially demolished in 1928. In 1966 the site was given in trust for the use of the general public.

Excavation of the site began in 1971, and became the largest to be carried out by modern methods on any European monastic site. It revealed the foundations and lower parts of the walls of the monastery buildings and the abbey church. Important finds included: a Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

doorway; a finely carved arcade

Arcade most often refers to:

* Arcade game, a coin-operated game machine

** Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade game's hardware

** Arcade system board, a standardized printed circuit board

* Amusement arcade, a place with arcade games

* ...

; a floor of mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

tiles, the largest floor area of this type to be found in any modern excavation; the remains of the kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

where the tiles were fired; a bell casting pit used for casting the bell; and a large medieval statue of Saint Christopher.

The priory was opened to the public as a visitor attraction in the 1970s. The 42-acre site, run by an independent charitable trust, includes a museum, the excavated ruins, and the surrounding garden and woodland. In 1984 the separate walled garden

A walled garden is a garden enclosed by high walls, especially when this is done for horticultural rather than security purposes, although originally all gardens may have been enclosed for protection from animal or human intruders. In temperate c ...

was redesigned and opened to the public. Norton Priory offers a programme of events, exhibitions, educational courses, and outreach projects. In August 2016, a larger and much extended museum opened.

History

Priory

In 1115 a community ofAugustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

canons was founded in the burh

A burh () or burg was an Old English fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new constru ...

of Runcorn

Runcorn is an industrial town and cargo port in the Borough of Halton in Cheshire, England. Its population in 2011 was 61,789. The town is in the southeast of the Liverpool City Region, with Liverpool to the northwest across the River Mersey. ...

by William fitz Nigel

William fitz Nigel (died 1134), of Halton Castle in Cheshire, England, was Constable of Chester and Baron of Halton within the county palatine of Chester ruled by the Earl of Chester.

Origins

Traditionally, he succeeded his father Nigel as bar ...

, the second Baron of Halton

The Barony of Halton, in Cheshire, England, comprised a succession of 15 barons and hereditary Constables of Chester under the overlordship of the Earl of Chester. It was not an English feudal barony granted by the king but a separate class of ...

and Constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, on the south bank of the River Mersey

The River Mersey () is in North West England. Its name derives from Old English and means "boundary river", possibly referring to its having been a border between the ancient kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. For centuries it has formed part ...

where it narrows to form the Runcorn Gap

The River Mersey () is in North West England. Its name derives from Old English and means "boundary river", possibly referring to its having been a border between the ancient kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. For centuries it has formed part ...

. This was the only practical site where the Mersey could be crossed between Warrington

Warrington () is a town and unparished area in the borough of the same name in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England, on the banks of the River Mersey. It is east of Liverpool, and west of Manchester. The population in 2019 was estimat ...

and Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liver ...

, and the archaeologists Fraser Brown and Christine Howard-Davis consider it likely that the canons cared for travellers and pilgrims crossing the river. They also speculate that William may have sought to profit from the tolls paid by these travellers.

The priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of mon ...

was the second religious house to be founded in the Earldom of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and ...

; the first was the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

St Werburgh's Abbey at Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, founded in 1093 by Hugh Lupus

Hugh d'Avranches ( 1047 – 27 July 1101), nicknamed ''le Gros'' (the Large) or ''Lupus'' (the Wolf), was from 1071 the second Norman Earl of Chester and one of the great magnates of early Norman England.

Early life and career

Hugh d'Avra ...

, the first Earl of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and a ...

. The priory at Runcorn had a double dedication, to Saint Bertelin and to Saint Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

. The authors of the ''Victoria County History

The Victoria History of the Counties of England, commonly known as the Victoria County History or the VCH, is an English history project which began in 1899 with the aim of creating an encyclopaedic history of each of the historic counties of En ...

'' suggest that the dedication to St Bertelin was taken from a Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

church already existing on the site. In 1134 William fitz William, the third Baron of Halton, moved the priory to a site in Norton Norton may refer to:

Places

Norton, meaning 'north settlement' in Old English, is a common place name. Places named Norton include: Canada

*Rural Municipality of Norton No. 69, Saskatchewan

*Norton Parish, New Brunswick

**Norton, New Brunswick, a ...

, a village to the east of Runcorn. The reasons for the move are uncertain. It may have been that fitz William wanted greater control of the strategic crossing of the Mersey at Runcorn Gap, or it may have been because the canons wanted a more secluded site. Nothing remains of the site of the original priory in Runcorn.

The site for the new priory was in damp, scrubby woodland. There is no evidence that it was agricultural land, or that it contained any earlier buildings. The first priority was to clear and drain the land. There were freshwater springs near the site, and these would have provided fresh running water for latrines and domestic purposes. They would also have been used to create watercourses and

The site for the new priory was in damp, scrubby woodland. There is no evidence that it was agricultural land, or that it contained any earlier buildings. The first priority was to clear and drain the land. There were freshwater springs near the site, and these would have provided fresh running water for latrines and domestic purposes. They would also have been used to create watercourses and moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that is dug and surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive ...

ed enclosures, some of which might have been used for orchards and herb gardens. Sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

for building the priory was available at an outcrop nearby, sand for mortar could be obtained from the shores of the River Mersey, and boulder clay

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists ...

on the site provided material for floor and roof tiles.

Excavation has revealed remnants of oak, some of it from trees hundreds of years old. It is likely that this came from various sources; some from nearby, and some donated from the forests at Delamere and Macclesfield

Macclesfield is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Bollin in the east of the county, on the edge of the Cheshire Plain, with Macclesfield Forest to its east ...

. The church and monastic buildings were constructed in Romanesque style.

The priory was endowed by William fitz Nigel with properties in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

and Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

, including the churches of St Mary, Great Budworth and St Michael, Chester. By 1195 the priory owned eight churches, five houses, the tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

of at least eight mills, the rights of common

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally com ...

in four townships, and one-tenth of the profits from the Runcorn ferry. The prior supplied the chaplain to the hereditary Constables of Chester and to the Barons of Halton.

During the 12th century, the main benefactors of the priory were the Barons of Halton, but after 1200 their gifts reduced, mainly because they transferred their interests to the Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

abbey at Stanlow, which had been founded in 1178 by John fitz Richard, the sixth baron. Archaeologist J. Patrick Greene

J. Patrick Greene is a British archaeologist and museum director. He served as Director of the Science and Industry Museum, in Manchester, England from 1983 to 2002, and then CEO of Museums Victoria in Australia from 2002 to 2017.

Biography

Green ...

states that it is unlikely that any of the Barons of Halton were buried in Norton Priory. The only members of the family known to be buried there are Richard, brother of Roger de Lacy, the seventh baron, and a female named Alice. The identity of Alice has not been confirmed, but Greene considers that she was the niece of William, Earl Warenne, the 5th Earl of Surrey and therefore a relative of the Delacy family, who were at that time the Barons of Halton. The earl made a grant to the priory of 30 shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence or ...

a year in order to "maintain a pittance

Pittance (through Old French ''pitance'' and from Latin ''pietas'', loving-kindness) is a gift to the members of a religious house for masses, consisting usually of an extra allowance of food or wine on occasions such as the anniversary of the dono ...

for her soul". As the role played by the Barons of Halton declined, so the importance of members of the Dutton family increased. The Duttons had been benefactors since the priory's foundation, and from the 13th century they became the principal benefactors. There were two main branches of the family, one in Dutton and the other in Sutton Weaver

Sutton Weaver is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester, in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. It is 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of Frodsham and 2.5 miles (4 km) south of Runcorn. According ...

. The Dutton family had their own burial chapel in the priory, and burial in the chapel is specified in three wills made by members of the family. The Aston family of Aston

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, England. Located immediately to the north-east of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority. It is approximately 1.5 miles from Birmingham City Centre.

History

Aston wa ...

were also important benefactors.

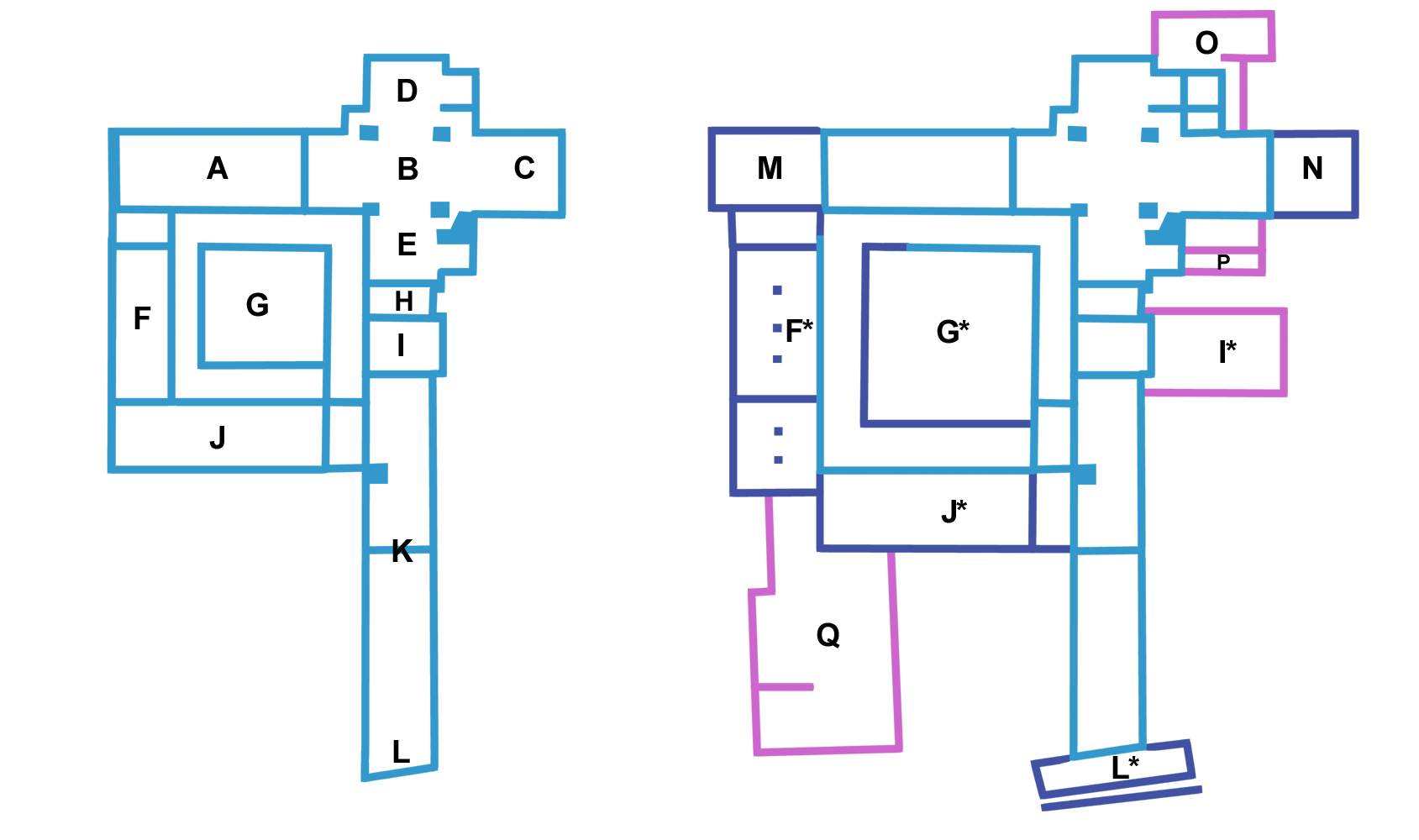

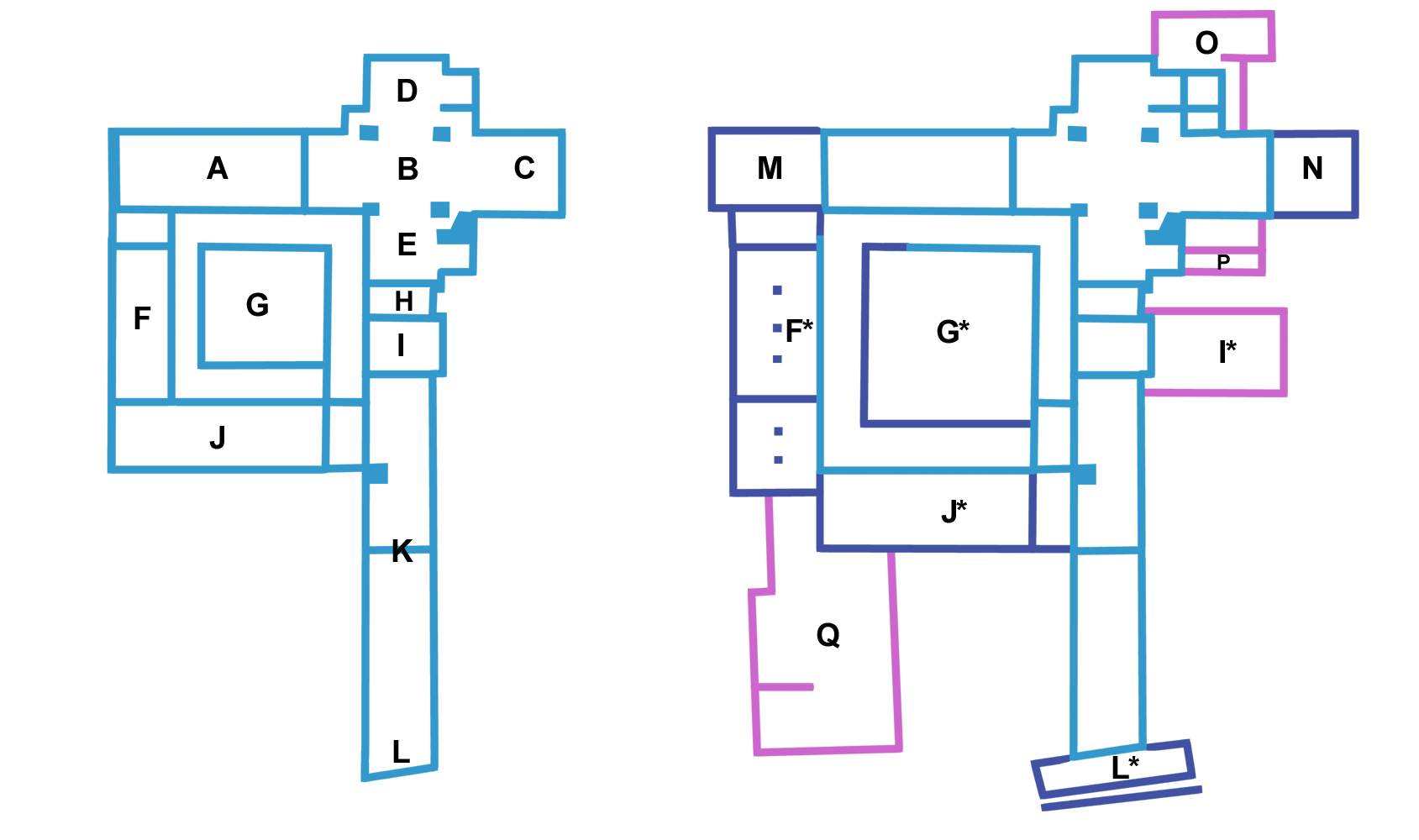

The priory buildings, including the church, were extended during the late 12th and early 13th centuries. It has been estimated that the original community would have consisted of 12 canons and the prior; this increased to around 26 members in the later part of the 12th century, making it one of the largest houses in the Augustinian order. By the end of the century the church had been lengthened, a new and larger chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

had been built (I* on the plan), and a large chapel had been added to the east end of the church (N). In about 1200 the west front of the church was enlarged (M), a bell tower was built and guest quarters were constructed. It is possible that the chapel at the east end was built to accommodate the holy cross of Norton, a relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

which was reputed to have miraculous healing powers. A fire in 1236 destroyed the timber-built kitchen (Q) and damaged the west range of the monastic buildings and the roof of the church. The kitchen was rebuilt and the other damage was rapidly repaired.

Abbey

During the first half of the 14th century, the priory suffered from financial mismanagement and disputes with the Dutton family, exacerbated by a severe flood in 1331 that reduced the income from the priory's lands. The direct effects of theBlack Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

are not known, but during the 1350s financial problems continued. These were party mitigated with the selling of the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

of the church at Ratcliffe-on-Soar

Ratcliffe-on-Soar is a village and civil parish in Nottinghamshire on the River Soar. It is part of the Rushcliffe district, and is the site of Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station. Nearby places are Kingston on Soar, Kegworth and Trentlock. With a ...

. Matters further improved from 1366 with the appointment of Richard Wyche as prior. He was active in the governance of the wider Augustinian order and in political affairs, and in 1391 was involved in raising the priory's status to that of a mitred abbey. A mitred abbey was one in which the abbot was given permission to use pontifical insignia, including the mitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in ...

, ring

Ring may refer to:

* Ring (jewellery), a round band, usually made of metal, worn as ornamental jewelry

* To make a sound with a bell, and the sound made by a bell

:(hence) to initiate a telephone connection

Arts, entertainment and media Film and ...

and pontifical staff, and to give the solemn benediction

A benediction (Latin: ''bene'', well + ''dicere'', to speak) is a short invocation for divine help, blessing and guidance, usually at the end of worship service. It can also refer to a specific Christian religious service including the expositio ...

provided a bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

was not present. It was rare for an Augustinian house to be elevated to this status. Out of about 200 Augustinian houses in England and Wales, 28 were abbeys and only seven of these became mitred. The only other mitred abbey in Cheshire was that of St Werburgh in Chester. In 1379 and in 1381 there were 15 canons at Norton and in 1401 there were 16, making it the largest Augustinian community in the northwest of England. By this time the barony of Halton had passed by a series of marriages to the duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of ...

. John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was an English royal prince, military leader, and statesman. He was the fourth son (third to survive infancy as William of Hatfield died shortly after birth) of King Edward ...

, the 1st Duke of Lancaster and 14th Baron of Halton, agreed to be the patron of the newly formed abbey. At this date the church was long; it was the second longest Augustinian church in northwest England, exceeded only by the long church at Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

. Towards the end of the 14th century, the abbey acquired a "giant" statue of Saint Christopher. Three wills from members of the Dutton family from this period survive; they are dated 1392, 1442 and 1527, and in each will money was bequeathed to the foundation.

The abbey's fortunes went into decline after the death of Richard Wyche in 1400. Wyche was succeeded by his

The abbey's fortunes went into decline after the death of Richard Wyche in 1400. Wyche was succeeded by his prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

, John Shrewsbury, who "does not seem to have done more than keep the house in order". Frequent floods had reduced its income, and in 1429 the church and other abbey buildings were described as being "ruinous". Problems continued through the rest of the 15th century, resulting in the sale of more advowsons. By 1496 the number of canons had been reduced to nine, and to seven in 1524. In 1522 there were reports of disputes between the abbot and the prior. The abbot was accused of "wasting the house's resources, nepotism, relations with women" and other matters, while the prior admitted to "fornication and lapses in the observation of the Rule

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Education

* Royal University of Law and Economics (RULE), a university in Cambodia

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule perta ...

". The prior threatened the abbot with a knife, but then left the abbey. The physical state of the buildings continued to deteriorate.

The records of the priory and abbey have not survived, but the excavations and the study of other documents have produced evidence of how the monastic lands were managed. The principal source of income came from farming. This income was required not only for the building and upkeep of the property, but also for feeding the canons, their guests, and visiting pilgrims. The priory also had an obligation from its foundation to house travellers fording the Mersey. It has been estimated that nearly half of the demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

lands were used for arable farming

Arable land (from the la, wikt:arabilis#Latin, arabilis, "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Al ...

. The grain grown on priory lands was ground by a local windmill and by a watermill outside the priory lands. Excavations revealed part of a stone handmill in the area used in the monastic kitchen. In addition to orchards and herb gardens in the moated enclosures, it is likely that beehives were maintained for the production of honey. There is evidence from bone fragments that cattle, sheep, pigs, geese and chickens were reared and consumed, but few bone fragments from deer, rabbits or hares have been discovered. Horseflesh was not eaten. Although few fish bones have been discovered, it is known from documentary evidence that the canons owned a number of local fisheries. The fuel used consisted of wood and charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

, and turf

Sod, also known as turf, is the upper layer of soil with the grass growing on it that is often harvested into rolls.

In Australian and British English, sod is more commonly known as ''turf'', and the word "sod" is limited mainly to agricultu ...

from marshes over which the priory had rights of turbary

Turbary is the ancient right to cut turf, or peat, for fuel on a particular area of bog. The word may also be used to describe the associated piece of bog or peatland and, by extension, the material extracted from the turbary. Turbary rights, whic ...

(to cut turf).

The events in 1536 surrounding the fate of the abbey at the dissolution of the monasteries are complicated, and included a dispute between Sir Piers Dutton

Sir Piers Dutton (died 17 August 1545) was the lord of the manor of Dutton from 1527 until his death. He was involved in the closing of Norton Abbey during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. He started rebuilding Dutton Hall in 1539.

E ...

, who was in a powerful position as the Sheriff of Cheshire

This is a list of Sheriffs (and after 1 April 1974, High Sheriffs) of Cheshire.

The Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the Sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most ...

, and Sir William Brereton, the deputy-chamberlain of Chester. Dutton's estate was next to that of the abbey, and Dutton plotted to gain some of its land from the Crown after the dissolution; while Brereton supported the abbot against Dutton and held the lucrative position of steward of the abbey. A campaign of vilification was directed at the canons, asserting that they were guilty of "debauched conduct". Then, in 1535, Dutton falsely accused the abbot and Brereton of issuing counterfeit coins. This charge was dismissed mainly because one of Dutton's witnesses was considered to be "unconvincing". Playing into Duttons' hands was the gross undervaluation of the abbey's assets as reported to the royal commissioners of the Valor Ecclesiasticus

The ''Valor Ecclesiasticus'' (Latin: "church valuation") was a survey of the finances of the church in England, Wales and English controlled parts of Ireland made in 1535 on the orders of Henry VIII. It was colloquially called the Kings books, a s ...

of 1535; as a result of which the net annual income of the abbey was recorded, falsely, as falling below the £200 () threshold that would subsequently be chosen for the first round of dissolutions in 1536, although whether this subterfuge was due to the machinations of Dutton or the abbot (or both) remains unclear. Brereton and the abbot appear to have attempted to have the dissolution cancelled subject to the payment of a fine, as was the case in large numbers of other houses in similar circumstances; but in the abbot's absence dissolution commissioners arrived unannounced at the abbey in early October 1536. There was considerable opposition, the commissioners being menaced by around 300 local people; for whom the abbot, rushing back, threw an impromptu feast complete with roasted ox. According to Dutton's account, after barricading themselves in a tower the commissioners managed to send a letter to Dutton, who arrived with a force of men in the middle of the night. Most of the rioters fled, but Dutton arrested the abbot and four of the canons, who were sent to Halton Castle

Halton Castle is a castle in the village of Halton, part of the town of Runcorn, Cheshire, England. The castle is on the top of Halton Hill, a sandstone prominence overlooking the village. The original building, a motte-and-bailey castle beg ...

and then to prison in Chester. Dutton sent a report of the events to Henry VIII; who demanded that if the abbot and canons had behaved as Dutton reported, they should be immediately executed as traitors. However, because the kings instructions had been conveyed by the Lord Chancellor in the form of letters to both Dutton and Brereton, the two faction leaders would be required to act together to effect them; with the consequence that Brereton was temporarily able to stall any such action by refusing to meet with Dutton. Events elsewhere in the country further delayed the execution and, following an intercession to Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charge ...

(whose own informal contacts had cast doubt on the reliability of Dutton's reports), the abbot and canons were discharged and awarded pensions. The abbey was made uninhabitable, the lead from the roof, the bell metal, and other valuable materials were confiscated for the king, and the building lay empty for nine years. The estate came into the ownership of the Crown, and it was managed by Brereton. From the evidence of damage to the tiled floor of the church, Brown and Howard-Davis conclude it is likely that the church was demolished at an early stage, but otherwise the archaeological evidence for this period is sparse and largely negative.

Country house

In 1545 the abbey and the manor of Norton were sold to Sir Richard Brooke for a little over £1,512 (). Brooke built a house in Tudor style, which became known as Norton Hall, using as its core the former abbot's lodgings and the west range of the monastic buildings. It is not certain which other monastic buildings remained when the abbey was bought by the Brookes; excavations suggest that the

In 1545 the abbey and the manor of Norton were sold to Sir Richard Brooke for a little over £1,512 (). Brooke built a house in Tudor style, which became known as Norton Hall, using as its core the former abbot's lodgings and the west range of the monastic buildings. It is not certain which other monastic buildings remained when the abbey was bought by the Brookes; excavations suggest that the cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

s were still present. A 17th-century sketch plan by one of the Randle Holme

Randle Holme was a name shared by members of four successive generations of a family who lived in Chester, Cheshire, England from the late years of the 16th century to the early years of the 18th century. They were all herald painters and genea ...

family shows that the gatehouse remained at that time, although almost all the church had been demolished. An engraving by the Buck brothers

Buck Brothers were a British three piece rock band. The band's sound is a mixture of pop and punk.

History

Buck Brothers formed early in 2005 via a chance meeting at the unlikely location of a Buddhist Disco in North London.

None of the mem ...

dated 1727 shows that little changed by the next century.

During the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

the house was attacked by a force of Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

. The Brookes were the first family in north Cheshire to declare allegiance to the Parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

side. Halton Castle

Halton Castle is a castle in the village of Halton, part of the town of Runcorn, Cheshire, England. The castle is on the top of Halton Hill, a sandstone prominence overlooking the village. The original building, a motte-and-bailey castle beg ...

was a short distance away, and was held by Earl Rivers

Earl Rivers was an English title, which has been created three times in the Peerage of England. It was held in succession by the families of Woodville (or Wydeville), Darcy and Savage.

History

The first creation was made for Richard Woodville, 1s ...

for the Royalists. In February 1643 a large force from the castle armed with cannon attacked the house, which was defended by only 80 men. Henry Brooke successfully defended the house, with only one man wounded, while the Royalists lost 16 men including their cannonier (gunner). They burnt two barns and plundered Brooke's tenants, but "returned home with shame and the hatred of the country".

At some time between 1727 and 1757 the Tudor house was demolished and replaced by a new house in

At some time between 1727 and 1757 the Tudor house was demolished and replaced by a new house in Georgian

Georgian may refer to:

Common meanings

* Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

** Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

** Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

**Georgian scripts, three scrip ...

style. The house had an L-plan, the main wing facing west standing on the footprint of the Tudor house, with a south wing at right-angles to it. The ground floor of the west wing retained the former vaulted

In architecture, a vault (French ''voûte'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground (street-level) area which is relatively open ...

of the west range of the medieval abbey, and contained the kitchens and areas for the storage of wines and beers. The first floor was the piano nobile

The ''piano nobile'' (Italian for "noble floor" or "noble level", also sometimes referred to by the corresponding French term, ''bel étage'') is the principal floor of a palazzo. This floor contains the main reception and bedrooms of the hou ...

, containing the main reception rooms. The west front was symmetrical, in three storeys, with a double flight of stairs leading up to the main entrance. Clearance of the other surviving remnants of the monastic buildings had started but the moated enclosures were still in existence at that time. A drawing dated 1770 shows that by then all these buildings and the moats had been cleared away, and the former fishponds were being used for pleasure boating. Between 1757 and the early 1770s modifications were made to the house, the main one being the addition of a north wing. According to the authors of the ''Buildings of England

The Pevsner Architectural Guides are a series of guide books to the architecture of Great Britain and Ireland. Begun in the 1940s by the art historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, the 46 volumes of the original Buildings of England series were published b ...

'' series, the architect responsible for this was James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

. Also between 1757 and 1770, the Brooke family built a walled garden

A walled garden is a garden enclosed by high walls, especially when this is done for horticultural rather than security purposes, although originally all gardens may have been enclosed for protection from animal or human intruders. In temperate c ...

at a distance from the house to provide fruit, vegetables and flowers. The family also developed the woodland around the house, creating pathways, a stream-glade and a rock garden. Brick-built wine bins were added to the undercroft, developing it into a wine cellar, and barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

ing was added to the former entrance hall to the abbey (which was known as the outer parlour), obscuring its arcade

Arcade most often refers to:

* Arcade game, a coin-operated game machine

** Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade game's hardware

** Arcade system board, a standardized printed circuit board

* Amusement arcade, a place with arcade games

* ...

.Morriss, R. in

During the mid-18th century, Sir Richard Brooke was involved in a campaign to prevent the Bridgewater Canal

The Bridgewater Canal connects Runcorn, Manchester and Leigh, Greater Manchester, Leigh, in North West England. It was commissioned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, to transport coal from his mines in Worsley to Manchester. It was ...

from being built through his estate. The Bridgewater Canal Extension Act had been passed in 1762, and it made allowances for limited disturbance to the Norton estate. However Sir Richard did not see the necessity for the canal and opposed its passing through his estate. In 1773 the canal was opened from Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

to Runcorn, except for across the estate, which meant that goods had to be unloaded and carted around it. Eventually Sir Richard capitulated, and the canal was completed throughout its length by March 1776.

By 1853 a service range had been added to the south wing of the house. In 1868 the external flight of stairs was removed from the west front and a new porch entrance was added to its ground floor. The entrance featured a

By 1853 a service range had been added to the south wing of the house. In 1868 the external flight of stairs was removed from the west front and a new porch entrance was added to its ground floor. The entrance featured a Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

doorway that had been moved from elsewhere in the monastery; Greene believes that it probably formed the entrance from the west cloister walk into the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

of the church. An exact replica of this doorway was built and placed to the north of the Norman doorway, making a double entrance. The whole of the undercroft was radically restored, giving it a Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

theme, adding stained glass windows and a medieval-style fireplace. The ground to the south of the house was levelled and formal gardens were established.

During the 19th century the estate was again affected by transport projects. In 1804 the Runcorn to Latchford Canal

The Runcorn to Latchford Canal (or Old Quay Canal or Old Quay Cut or Black Bear Canal) was a man-made canal that ran from Runcorn, to the Latchford area of Warrington. It connected the Mersey and Irwell Navigation to the River Mersey at Runcor ...

was opened, replacing the Mersey and Irwell Navigation

The Mersey and Irwell Navigation was a river navigation in North West England, which provided a navigable route from the Mersey estuary to Salford and Manchester, by improving the course of the River Irwell and the River Mersey. Eight locks were ...

; this cut off the northern part of the estate, making it only accessible by a bridge. The Grand Junction Railway

The Grand Junction Railway (GJR) was an early railway company in the United Kingdom, which existed between 1833 and 1846 when it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Western Railway. The line built by the company w ...

was built across the estate in 1837, followed by the Warrington and Chester Railway, which opened in 1850; both of these lines affected the southeast part of the estate. In 1894, the Runcorn to Latchford Canal was replaced by the Manchester Ship Canal

The Manchester Ship Canal is a inland waterway in the North West of England linking Manchester to the Irish Sea. Starting at the Mersey Estuary at Eastham, near Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, it generally follows the original routes of the river ...

, and the northern part of the estate could only be accessed by a swing bridge

A swing bridge (or swing span bridge) is a movable bridge that has as its primary structural support a vertical locating pin and support ring, usually at or near to its center of gravity, about which the swing span (turning span) can then pi ...

. The Brooke family left the house in 1921, and it was almost completely demolished in 1928. Rubble from the house was used in the foundations of a new chemical works. During the demolition, the undercroft was retained and roofed with a cap of concrete. In 1966 the current Sir Richard Brooke gave Norton Priory in trust for the benefit of the public.

Excavations and museum

In 1971 J. Patrick Greene was given a contract to carry out a six-month excavation for Runcorn Development Corporation as part of a plan to develop a park in the centre of Runcorn New Town. The site consisted of a area of fields and woods to the north of theBridgewater Canal

The Bridgewater Canal connects Runcorn, Manchester and Leigh, Greater Manchester, Leigh, in North West England. It was commissioned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, to transport coal from his mines in Worsley to Manchester. It was ...

. Greene's initial findings led to his being employed for a further 12 years to supervise a major excavation of the site. The buildings found included the Norman doorway with its Victorian addition and three medieval rooms. Specialists were employed and local volunteers were recruited to assist with the excavation, while teams of supervised prisoners were used to perform some of the heavier work. The area excavated exceeded that at any European monastic site that used modern methods. The Development Corporation decided to create a museum on the site, and in 1975 Norton Priory Museum Trust was established.

In 1989 Greene published his book about the excavations entitled ''Norton Priory: The Archaeology of a Medieval Religious House''. Further work has been carried out, recording and analysing the archaeological findings. In 2008 Fraser Brown and Christine Howard-Davis published ''Norton Priory: Monastery to Museum'', in which the findings are described in more detail. Howard-Davis was largely responsible for the post-excavation assessment and for compiling a database for the artefacts and, with Brown, for their analysis.

Findings from excavations

Priory 1134–1236

The excavations have revealed information about the original priory buildings and grounds, and how they were subsequently modified. A series of ditches was found that would have provided a supply of fresh water and also a means for drainage of a relatively wet site. Evidence of the earliest temporary timber buildings in which the canons were originally housed was found in the form of 12th-century post pits. Norton Priory is one of few monastic sites to have produced evidence of temporary quarters. The remains of at least seven temporary buildings have been discovered. It is considered that the largest of these, because it had more substantial foundations than the others, was probably thetimber-framed

Timber framing (german: Holzfachwerk) and "post-and-beam" construction are traditional methods of building with heavy timbers, creating structures using squared-off and carefully fitted and joined timbers with joints secured by large wooden ...

church; another was most likely the gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the mos ...

, and the other buildings provided accommodation for the canons and the senior secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

craftsmen.

The earliest masonry building was the church, which was constructed on shallow foundations of

The earliest masonry building was the church, which was constructed on shallow foundations of sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

rubble and pebbles on boulder clay

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists ...

. The walls were built in local red sandstone with ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruv ...

faces and a rubble and mortar core. The ground plan of the original church was cruciform

Cruciform is a term for physical manifestations resembling a common cross or Christian cross. The label can be extended to architectural shapes, biology, art, and design.

Cruciform architectural plan

Christian churches are commonly described ...

, and consisted of a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

without aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

s, a choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

at the crossing with a tower above it, a square-ended chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ove ...

, and north and south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building withi ...

s, each with an eastern chapel. The total length of the church was and the total length across the transepts was , giving a ratio of 2:1. The walls of the church were wide at the base, and the crossing tower was supported on four piers Piers may refer to:

* Pier, a raised structure over a body of water

* Pier (architecture), an architectural support

* Piers (name), a given name and surname (including lists of people with the name)

* Piers baronets, two titles, in the baronetages ...

.

The other early buildings were built surrounding a cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

to the south of the church. The east range incorporated the chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

and also contained the sacristy

A sacristy, also known as a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christian churches for the keeping of vestments (such as the alb and chasuble) and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records.

The sacristy is usually located ...

, the canons' dormitory and the reredorter

The reredorter or necessarium (the latter being the original term) was a communal latrine found in mediaeval monasteries in Western Europe and later also in some New World monasteries.

Etymology

The word is composed from dorter and the Middle En ...

. The upper storey of the west range provided living accommodation for the prior and an area where secular visitors could be received. In the lower storey was the undercroft where food and fuel were stored. The south range contained the refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminaries. The name derives from the La ...

, and at a distance from the south range stood the kitchen. Evidence of a bell

A bell is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be made by an inter ...

foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

dating from this period was found to the north of the church. It is likely that this was used for casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a ''casting'', which is ejected ...

a tenor bell. A few moulded stones from this early period were found. These included nine blocks that probably formed part of a corbel table

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

. There were also two beak-head voussoir

A voussoir () is a wedge-shaped element, typically a stone, which is used in building an arch or vault.

Although each unit in an arch or vault is a voussoir, two units are of distinct functional importance: the keystone and the springer. The ...

s; this type of voussoir is rare in Cheshire, and has been found in only one other church in the county.

Considerable expansion occurred during the last two decades of the 12th century and the first two or three decades of the 13th century. The south and west ranges were demolished and rebuilt, enlarging the cloister from about by to about by . This meant that a door in the south wall of the church had to be blocked off and a new highly decorated doorway was built at the northeast corner of the cloister; this doorway has survived. The lower storey of the west range, the other standing remains of the priory, also dates from this period; it comprises the cellarer's undercroft and a passage to its north, known as the outer parlour. The outer parlour had been the entrance to the priory from the outside world, and was "sumptuously decorated" so that "the power and wealth of the priory could be displayed in tangible fashion to those coming from the secular world". The undercroft, used for storage, was divided into two chambers, and its decoration was much plainer. The upper floor has been lost; it is considered that this contained the prior's living quarters and, possibly, a chapel over the outer parlour. A new and larger reredorter was built at the end of the east range, and it is believed that work might have started on a new chapter house. A system of stone drains was constructed to replace the previous open ditches. The west wall of the church was demolished and replaced by a more massive structure, thick at the base. The east wall was also demolished and the chancel was extended, forming an additional area measuring approximately by .

Priory and abbey 1236–1536

The excavation revealed evidence of the fire of 1236, including ash, charcoal, burnt planks and a burnt wooden bowl. It is thought that the fire probably started in the timber-built kitchens at the junction of the west and south ranges, and then spread to the monastic buildings and church. Most of the wood in the buildings, including the furnishings and roofs, would have been destroyed, although the masonry walls remained largely intact. The major repairs required gave an opportunity for the extension of the church by the addition of new chapels to both of the transepts, and its refurbishment in a manner even grander than previously. The cloister had been badly damaged in the fire and its arcade was rebuilt on the previous foundations. The new arcade was of "very high quality and finely wrought construction". Brown and Howard-Davis state that the kitchens were rebuilt on the same site and it appears that they were rebuilt in timber yet again. Excavations have found evidence of a second bell foundry in the northwest of the priory grounds. The date of this is uncertain but Greene suggests that it was built to cast a new bell to replace the original one that was damaged in the fire. Later in the 13th century another chapel was added to the north transept. Accommodation for guests was constructed to the southwest of the monastic buildings. In the later part of the 13th century and during the following century the chapel in the south transept was replaced by a grander two-chambered chapel. This balanced the enlarged chapels in the north transept, restoring the church's cruciform plan. Around this time the east end of the church was further extended when areliquary

A reliquary (also referred to as a ''shrine'', by the French term ''châsse'', and historically including ''wikt:phylactery, phylacteries'') is a container for relics. A portable reliquary may be called a ''fereter'', and a chapel in which it i ...

chapel was added measuring about by . A guest hall was built to the west of the earlier guest quarters. After the status of the foundation was elevated from a priory to an abbey, a tower house

A tower house is a particular type of stone structure, built for defensive purposes as well as habitation. Tower houses began to appear in the Middle Ages, especially in mountainous or limited access areas, in order to command and defend strateg ...

was added to the west range. This is shown on the engraving by the Buck brothers, but it has left little in the way of archaeological remains. The church was extended by the addition of a north aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

. There is little evidence of later major alterations before the dissolution. There is evidence to suggest that the cloister was rebuilt, and that alterations were made to the east range.

Burials

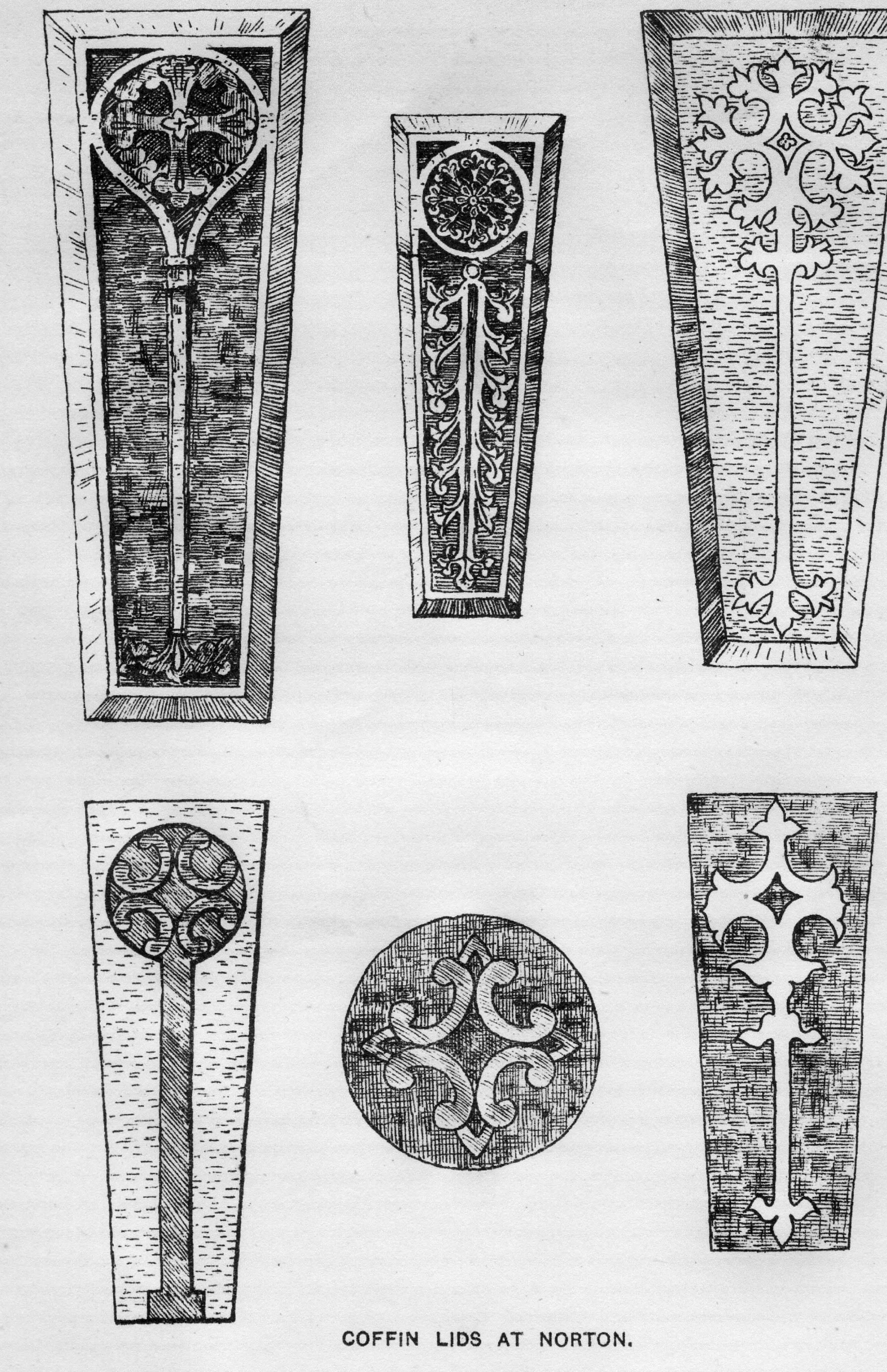

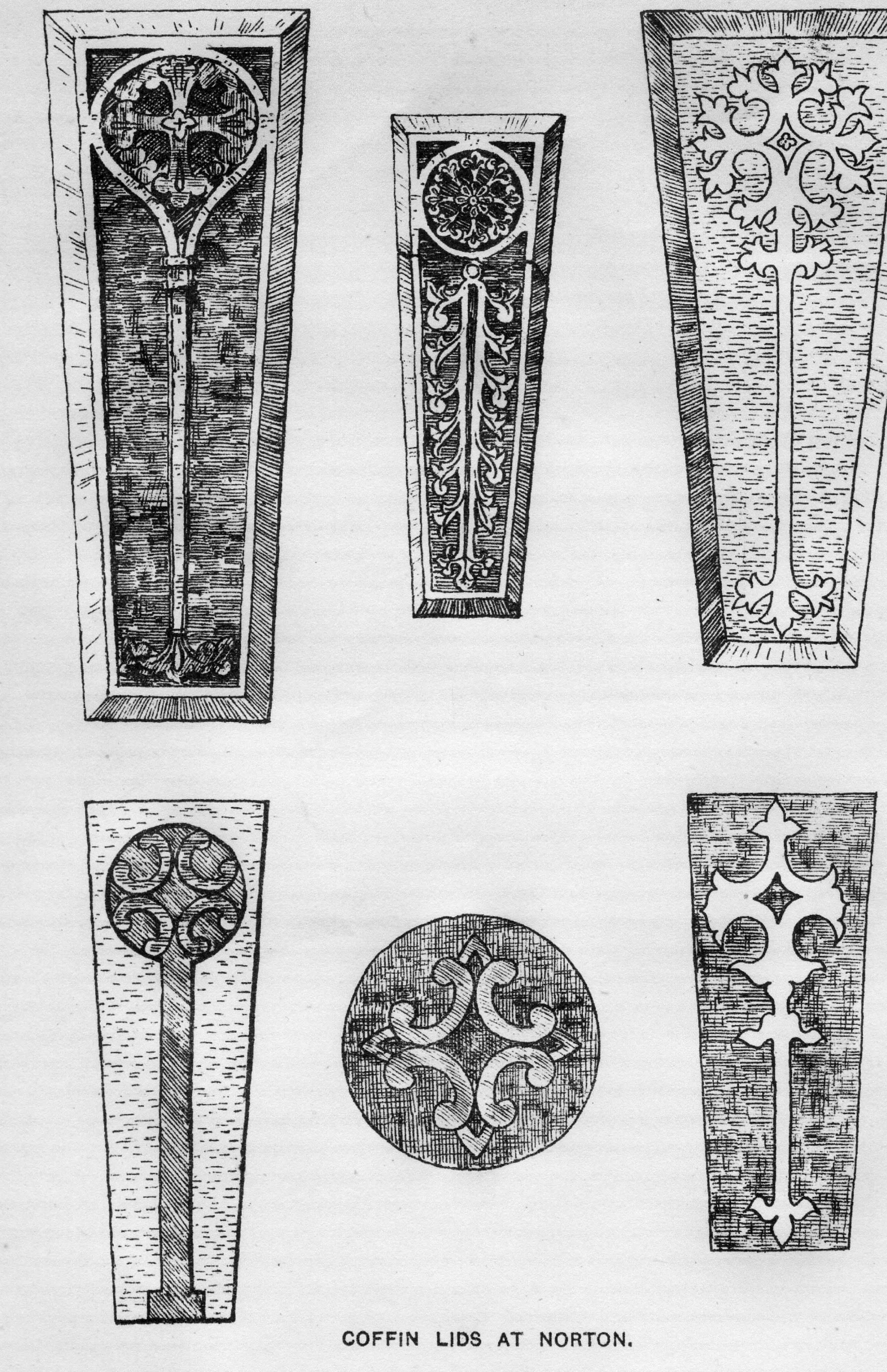

The excavations revealed information about the burials carried out within the church and the monastic buildings, and in the surrounding grounds. They are considered to be "either those of Augustinian canons, privileged members of their lay household, or of important members of the Dutton family". Most burials were in stone coffins or in wooden coffins with stone lids, and had been carried out from the late 12th century up to the time of the dissolution. The site of the burial depended on the status of the individual, whether they were clerical or lay, and their degree of importance. Priors, abbots, and high-ranking canons were buried within the church, with those towards the east end of the church being the most important. Other canons were buried in a graveyard outside the church, in an area to the south and east of the chancel. Members of the laity were buried either in the church, towards the west end of the nave or in the north aisle, or outside the church around its west end. It is possible that there was a lay cemetery to the north and west of the church. The addition of the chapels to the north transept, and their expansion, was carried out for the Dutton family, making it their burial chapel, or family

The excavations revealed information about the burials carried out within the church and the monastic buildings, and in the surrounding grounds. They are considered to be "either those of Augustinian canons, privileged members of their lay household, or of important members of the Dutton family". Most burials were in stone coffins or in wooden coffins with stone lids, and had been carried out from the late 12th century up to the time of the dissolution. The site of the burial depended on the status of the individual, whether they were clerical or lay, and their degree of importance. Priors, abbots, and high-ranking canons were buried within the church, with those towards the east end of the church being the most important. Other canons were buried in a graveyard outside the church, in an area to the south and east of the chancel. Members of the laity were buried either in the church, towards the west end of the nave or in the north aisle, or outside the church around its west end. It is possible that there was a lay cemetery to the north and west of the church. The addition of the chapels to the north transept, and their expansion, was carried out for the Dutton family, making it their burial chapel, or family mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

, and the highest concentration of burials was found in this part of the church. It is considered that the north aisle, built after the priory became an abbey, was added to provide a burial place for members of the laity.

The excavations revealed 49 stone coffins, 30 coffin lids, and five headstones. Twelve of the lids were carved in high relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

, with designs including flowers or foliage. One lid depicts an oak tree issuing from a human head in the style of a green man

The Green Man is a legendary being primarily interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, representing the cycle of new growth that occurs every spring. The Green Man is most commonly depicted in a sculpture, or other representation of a face which is ...

, another has a cross, a dragon and a female effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...